ARFF Daily News

Published on:

Friday the 10th of January, 2025

Civilian drone grounds LA firefighting plane after collision over Palisades fire

By Ian Molyneaux

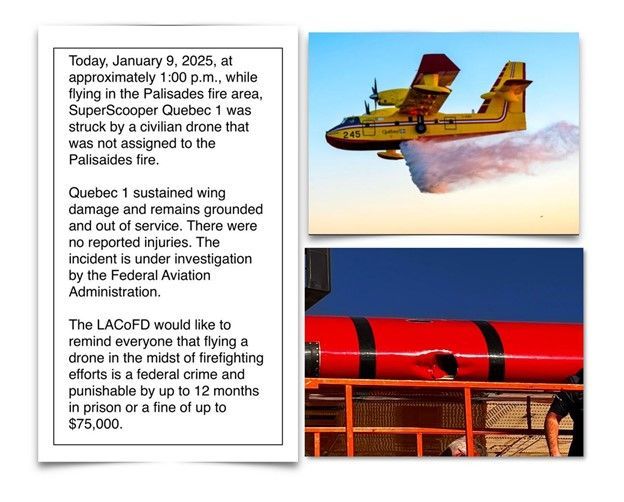

A Los Angeles aircraft has been grounded and pulled from firefighting service in the United States (US) after being hit by a civilian drone.

According to the LA County Fire Department, the Canadair CL-415 ‘Super Scooper’ was struck on January 10, 2025, at 13:30, local time, while operating in the ‘Palisades’ fire area.

The grounding of the lifesaving aircraft will come as a massive blow to the LA region, as firefighters try to defend homes and businesses from the devastating fires that have so far resulted in the deaths of ten people.

The Super Scooper, Quebec 1, was struck on its wing and sustained damage during the incident, though thankfully resulted in no injuries.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is investigating the incident and reminded the public that it is a federal crime to interfere with firefighting efforts on public lands. If found guilty, a person could face up to 12 months in prison and a civil penalty.

In a statement, the FAA said: “The FAA can impose a civil penalty of up to $75,000 against any drone pilot who interferes with wildfire suppression, law enforcement or emergency response operations when temporary flight restrictions (TFRs) are in place.”

The regulator added: “The FAA treats these violations seriously and immediately considers swift enforcement action for these offenses. The FAA has not authorized anyone unaffiliated with the Los Angeles firefighting operations to fly drones in the TFRs.”

In response to the incident, LA County Fire Chief Anthony Marrone has declared that the FBI would deploy technology in the area to combat any drones trying to capture footage of the five remaining blazes.

Governor of California Gavin Newsom has said that at least six air tankers and 40 helicopters are taking part in the operations, along with over 8,000 personnel.

There are currently five fires burning in the Los Angeles area, with firefighters making some significant headway in the last 12 hours as winds have dropped.

The newest fire, ‘Kenneth’, which broke out on January 8, 2025, is now 35% contained, while the ‘Hurst’ fire near Santa Clarita is now 37% contained.

The largest fire, ‘Palisades’, is now 6% contained and the ‘Lidia’ fire 75% contained. The ‘Eaton’ fire remains the only blaze that firefighters have so far been unable to contain.

https://www.aerotime.aero/articles/los-angeles-fires-firefighting-aircraft-collision-drone

China Certifies 4-Seat Commercial Electric Aircraft

All-electric RX4E receives type certification from the country’s civil aviation regulator and is claimed to be first of its kind to be cleared for commercial flight.

Jack Daleo

China has certified the world’s first electric aircraft for commercial flight, according to the operator of the model.

The RX4E—a four-passenger, battery-electric design developed by Rhyxeon General Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of Liaoning General Aviation Academy in China—received type certification from the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC), per a social media post by operating partner Volar Air Mobility.

Volar said the aircraft is the world’s first electric model certified for commercial flight under CAAC’s Part 23 regulations for normal aircraft, an analog to the FAA’s rule. While some electric designs, such as Pipistrel’s Velis Electro, have been certified for flight training, none have been approved to carry passengers or cargo.

FLYING interviewed Volar CEO Henry Hooi in April in Abu Dhabi, one of several locations worldwide it aims to fly the zero-emission aircraft. Hooi said the company will initially target RX4E operations in Southeast Asia before expanding to Africa and the Middle East, honing in on regions with traditionally poor aviation access. Use cases for the design, he said, might include private aviation, island hopping, tourism, agriculture, aerial photography, and even medical evacuations.

Rhyxeon, the manufacturer of the RX4E, first flew the aircraft with Liaoning in 2019. According to its website, the design has a range of about 186 sm (162 nm) and flight endurance of 1.5 hours, cruising around 137 mph (120 knots) with a payload of about 680 pounds. Hooi said its batteries can be swapped out in about 10 minutes.

The Volar CEO described the RX4E as a short takeoff and landing (STOL) model, with a minimum takeoff and landing distance just under 1,250 feet. He said that configuration makes the design easier to certify than the electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) air taxis being developed by manufacturers such as Archer Aviation and Joby Aviation in the U.S.

Volar told the South China Morning Post it has an agreement with Rhyxeon to commercialize the RX series of aircraft—which includes the RX4E and several other, smaller electric models—in 15 countries, including manufacturing operations.

Volar did not immediately respond to FLYING’s request for comment.

NTSB Prelim: Cessna 208B

The Instructor Pilot Responded By Saying: “We Are…We Have…We Are Out Of Control Here.”

Location: Honolulu, HI Accident Number: ANC25FA010

Date & Time: December 17, 2024, 15:15 Local Registration: N689KA

Aircraft: Cessna 208B Injuries: 2 Fatal

Flight Conducted Under: Part 91: General aviation - Instructional

On December 17, 2024, about 1515 Hawaii-Aleutian Standard time, a turbine-powered Cessna 208B airplane, N689KA, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Honolulu, Hawaii. The two pilots onboard were fatally injured. The airplane was operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 instructional flight.

According to the operator, Kamaka Air, the instructor pilot, seated in the left seat, and the pilot receiving instruction, seated in the right seat, departed the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (PHNL), Honolulu, at 1514. The purpose of the flight was to provide the pilot receiving instruction with additional training as part of the operator’s Second-In-Command training program. The planned flight was expected to go to Lanai Airport (PHNY), Lanai City, Hawaii, to perform flight maneuvers as well as practice instrument approach procedures. The operator reported that about 80 gallons of fuel was added to each wing tank just prior to departure. According to archived air traffic control communications, the airplane was cleared to depart runway 4L and was expected to follow the published Visual Flight Rules (VFR) Shoreline Six departure. The procedure called for departing traffic to fly runway heading, then turn right.

A preliminary review of archived voice communication information from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) revealed that shortly after departure, the Honolulu tower controller contacted the airplane and asked to confirm if they were turning right. The instructor pilot responded by saying: “we are…we have…we are out of control here.”

The accident airplane was equipped with Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS–B), which provides position information via satellite navigation or other sensors and periodically broadcasts it, enabling the airplane to be tracked. The accident airplane was also equipped was Spidertracks, which enabled real-time flight tracking, automated flight watch, two-way communication, and flight data monitoring (FDM) for the airplane. According to the ADS-B data and Spidertracks data, the airplane departed runway 4L, and near the departure end of the runway the airplane immediately began a left turn.

As the airplane continued a shallow climbing left turn, it eventually passed over an industrial area to the northeast of PHNL. As the flight progressed on a north-northeasterly heading, the left turn continued, and the airplane turned to a south westerly heading. The airplane’s left turn continued to steepen, and it eventually descended nose down into the industrial area just north of PHNL.

The airplane subsequently impacted an abandoned concrete building about 1,975 ft from the departure end of the runway. The left wing made initial contact with one of the large air conditioner units on the roof. The airplane then struck a concrete stairwell structure located on the roof of the abandoned building, then it continued into an adjacent parking lot to the south of the building. A postcrash fire ensued, which incinerated much of the wreckage.

The main wreckage came to rest about 120 feet beyond the initial impact point. The airplane’s empennage was separated during the impact sequence, and it was located in the upper portion of the stairwell structure near the roof of the building. Outboard portions of the airplane’s left wing were found on the roof of the building, near the initial impact point. The fuselage, and both wings were located in the parking lot to the south of the building.

The flight control system exhibited multiple breaks of the control cables due to impact and fire related damage. Sections of the flight control system were retained for further examination. The right wing was impact separated and located in a ditch about 100 ft from the main wreckage. The majority of the left wing was found in the main wreckage, underneath an aft section of the fuselage. The left flap was not observed in the main wreckage and was likely consumed in the post impact fire. The left wing was separated from the fuselage.

The engine core of the Pratt and Whittney PT6 turbine engine was found in the main wreckage site in front of the cockpit. The Aircraft Data Acquisition System (ADAS), which monitors, and auto-archives critical flight parameters was found in the area of the cockpit wreckage. However, the ADAS housing was breached and its circuit cards exhibited thermal damage. The ADAS housing was retained for further examination. One propeller blade was found in the stairwell structure the airplane impacted. The two remaining propeller blades were found in the main wreckage. The propeller hub was fractured in multiple locations and was found near the right wing.

The instructor pilot held a commercial pilot certificate with ratings for Airplane Single Engine Land (ASEL), Airplane Multiengine Land (AMEL), and Instrument airplane. In addition, he was a certificated flight instructor for single engine airplanes. Furthermore, he reported 1746 total hours of civilian flight experience and 376 hours in the last six months as of his last medical exam, which was performed on December 12, 2024. The pilot was issued a First-Class medical certificate without limitations.

The pilot receiving instruction held a commercial pilot certificate with ratings for Airplane Single Engine Land (ASEL) and Instrument airplane. Furthermore, he did not report his civilian flight experience as of his last medical exam, which was performed on August 8, 2024, however the operator reported his civilian flight experience to be about 340 hours total. The pilot was issued a First-Class medical certificate without limitations.

The accident sequence was captured by numerous security cameras, vehicle dash-mounted cameras, and other video recording devices. The various recordings were subsequently provided to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigative team. The various recorded video footage captured the airplane departing runway 4L and beginning a shallow left turn which appeared to steepen significantly prior to impact.

The archived video recordings were sent the NTSB’s vehicle recorders laboratory in Washington D.C., and a detailed NTSB video study is pending.

Two investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board's (NTSB) Alaska Regional Office, along with a senior aerospace engineer from Washington D.C., responded to the accident site and examined the airplane wreckage on December 18-22. During the detailed on-scene examination, the investigative team retained various components for additional examination and testing, and results are pending

FMI: www.ntsb.gov

Today in History

30 Years ago today: On 10 January 1995 Intercontinental de Aviación flight 256, a DC-9-10, crashed while on approach to Cartagena-Rafael Núñez Airport, Colombia, killing 51 occupants; one passenger survived the accident.

Date: Tuesday 10 January 1995

Time: 19:38

Type: Douglas DC-9-14

Owner/operator: Intercontinental de Aviación

Registration: HK-3839X

MSN: 45742/26

Year of manufacture: 1966

Total airframe hrs: 65084 hours

Cycles: 69716 flights

Engine model: P&W JT8D-7A

Fatalities: Fatalities: 51 / Occupants: 52

Other fatalities: 0

Aircraft damage: Destroyed, written off

Category: Accident

Location: near Maria La Baja - Colombia

Phase: Approach

Nature: Passenger - Scheduled

Departure airport: Bogotá-Eldorado Airport (BOG/SKBO)

Destination airport: Cartagena-Rafael Núñez Airport (CTG/SKCG)

Investigating agency: Aerocivil

Confidence Rating: Accident investigation report completed and information captured

Narrative:

Intercontinental de Aviación flight 256, a DC-9-10, crashed while on approach to Cartagena-Rafael Núñez Airport, Colombia, killing 51 occupants; one passenger survived the accident.

Flight ITC256 was scheduled to depart at 12:10 on a service to Cartagena and San Andres Island. The flight was delayed because of a malfunction on the previous flight. Maintenance work had to be carried out on the electrical system.

The flight finally departed at 18:45 after a delay of over six hours. At 19:09 the contacted the Bogota Center controller and reported en route at FL310. At 19:26 Barranquilla Control cleared the flight to start the descent from FL310 to FL140 and to report passing FL200. They passed FL200 at 19:33 and were instructed to contact Barranquilla Approach. One minute later, the flight was cleared further down to 8000 feet and to report passing 12.000 feet. This was the last radio contact with the flight. At 19:38 hours the crew of Aerocorales Flight 209 (a Cessna Caravan) reported that they saw "the lights of an airplane in rapid descend", followed by a ground explosion. The airplane came down in a marshy lagoon 56 km from Cartagena Airport. Investigation revealed that the no. 1 altimeter indicated 16.200 feet on impact.

PROBABLE CAUSE:

The probable cause of this accident was the loss of situational awareness by the crew.

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS:

Contributing to the loss of Vertical Situational Awareness, was the failure of the altimeter Number one during the descent, the lack of light in the altimeter Number two, the ineffectiveness of the Altitude Alert due to the failure of the altimeter Number one, the lack of radar service in the area, the complacency of the command crew because of good weather conditions, flight training that may not have been authorized by the company, the failure of the ground proximity warning system (GPWS), or lack of crew reaction time to respond to this alarm.

Mailing Address

Subscribe to our newsletter

Contact Us

We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Please try again later.